Please call 402-874-9900 or email OpalM@LewisandClarkVisitorCenter.org to order.

The Era of Pre-steam River Travel on Our Inland Waterways

by: Butch Bouvier

Terminologies are confusing for pre-steam era inland waterways craft. As in the case of the Lewis and Clark Expedition Barge, which has been identified as a keelboat for most of the 200 years since the expedition, many other craft are misunderstood. The French term Pirogue pronounced Pee-row has been applied to just about every craft that ever plied our rivers. In reality a pirogue is a small one or two man double ended canoe with slab sides and flat bottomed. The French boat crews of the L&C expedition were most probably the culprits who inserted the word Pirogue into the journals of the captains and Sergeants of that famous Expedition. They seem to refer to anything that floats on fresh water as a pirogue. One thi ng that indicates that these men were following the lead of the Frenchmen rather than using a term that they understood or had used before is the fact that between them they spelled it 12 different ways.

ng that indicates that these men were following the lead of the Frenchmen rather than using a term that they understood or had used before is the fact that between them they spelled it 12 different ways.

Most Pirogues were quickly built with simple tools as were most river craft built along the banks of our inland waterways, from  pit sawn lumber and as often as not by guys who may never have built a boat. If you examine paintings and sketches from the era you will see the resemblance between the French Pirogue and what we call Mackinaw boats or Bateaus. The Mackinaws of the western Rivers were easily built from green lumber, generally flat bottomed with a hard chine and slab sides. We call this the basic boat design or quick, down and dirty boat building. From the early 1700’s through the late 1800’s the concept of “We need a boat and in a hurry and we have to build it of available materials” remained the same as these pictures from the late 1800’s Alaskan gold rush era show. Most of these boats were built to use once on a one way journey but unlike flat boats which were little more than rafts with sides, they could go up stream when required but with their tubby design they fought the current when going against it. I have heard many times that these Craft were dismantled for their lumber when they reached their destination. There is probably some truth to this on occasion, but flat boats would lend themselves much more readily to house building after being used as a boat as their timbers are straight and usually pretty heavy. The mackinaw style boat will have thinner planks which are bent in at the bow and often the stern while green. Take them off a few months later and they will remain bent. I guess if your building a round house it’s okay.

pit sawn lumber and as often as not by guys who may never have built a boat. If you examine paintings and sketches from the era you will see the resemblance between the French Pirogue and what we call Mackinaw boats or Bateaus. The Mackinaws of the western Rivers were easily built from green lumber, generally flat bottomed with a hard chine and slab sides. We call this the basic boat design or quick, down and dirty boat building. From the early 1700’s through the late 1800’s the concept of “We need a boat and in a hurry and we have to build it of available materials” remained the same as these pictures from the late 1800’s Alaskan gold rush era show. Most of these boats were built to use once on a one way journey but unlike flat boats which were little more than rafts with sides, they could go up stream when required but with their tubby design they fought the current when going against it. I have heard many times that these Craft were dismantled for their lumber when they reached their destination. There is probably some truth to this on occasion, but flat boats would lend themselves much more readily to house building after being used as a boat as their timbers are straight and usually pretty heavy. The mackinaw style boat will have thinner planks which are bent in at the bow and often the stern while green. Take them off a few months later and they will remain bent. I guess if your building a round house it’s okay.

A dug out is a dug out and that’s all. They can be larger in some areas due too larger trees, and they can be filled with hot rocks and water once completed to spread them and gain more stability, and they can be very fancy when made from large cedars or Redwoods on the west coast but they are still dugouts. They can be lashed together for stability and fitted with sails and they are still dugouts. You can take logs and fit them together as large planks to make a larger craft and these are called log canoes and were popular on the east coast for awhile but I have found no evidence that this method of building traveled too far west. If you were along a river in the wilderness and did not have a pit saw you could put a log canoe together, but given the choice your best bet would be sawn planks and a flat bottom and a hard chine.

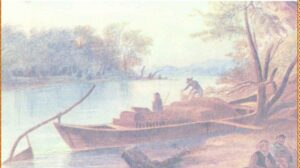

Now we come to river craft which were not quickly thrown together but rather constructed at areas known for boat building by folks who knew how to do it. These are you Barges and Keelboats. Although they were both built to haul cargo, they differed in design because barges were generally designed for massive amounts of cargo, sometimes stacked far above the waterline downstream loaded and re- turning upstream generally empty. This section of a painting done about 1800 shows a small Barge loaded with cotton bales. The hull design for a Barge created a large foot print which reduces the draft and gives great stability but increases the drag.

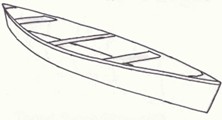

Keelboats were purpose built craft in yards designed to build boats; by folks who were very good at their trade. They needed to have the capacity to carry much cargo both up and down stream. They had to run in shallow water and needed as shallow a draft as possible. Their hull shape reflects this trade off between streamlining and cargo capacity with shallow draft. While overall design of the rest of the boat meets the challenges that a western river keelboat would encounter in its travels.

Eastern Rivers sisters from bow to stern are: A set of rowing benches in the bow, cleated walkways along the cabin, a short but stout mast usually fitted with rat lines so a lookout could get far above the deck to see shallow water and what’s around the next bend. Most often the mast could be easily and quickly let down for low trees. A small row boat of some sort for getting to shore when necessary and at the stern a platform for the steersman so he could see above the cabin and a rudder/sweep. The rudder/sweep was on a gimble which allowed it to be moved up and down as well as left to right so it would bounce over river debris without snapping off and could be used in a sweeping motion to move the boat left or right when going downstream where a rudder is all but worthless. The hull was slightly rounded at the chine but pretty much flat on the bottom and she would be double ended to allow water to flow around her easily thus reducing upriver drag. A heavy keel would run the length of the boat protruding below the main hull maybe as much as 8 inches. This keel provided strength and protection for the boat. When she grounded on a sand bar or a beaching only the keel would touch. This would allow her to be backed off easily. Also, while traveling the bow of the boat would be loaded down more so she would be protected from a hard belly grounding which could break her back. If the bow clears an obstacle, then the rest of the boat will, a very safe way to travel up stream. Going down stream it is a little hairy at times but still the best policy to keep the bow low. In down stream travel the biggest danger is sticking the bow and having the stern start swinging around, cross ways to a bar in current is not a good thing.

Moving these craft up and down the rivers was no easy task. The methods used were varied and determined by many factors such as the depth of the water, the condition of the bottom, the condition of the shore line, the weather, and the shape of the river.

They include the following:

Cordelling; is basically pulling the boat up stream with a long rope but involves much more than just that. Imagine your flying a large green kite. The blue line on the kite corresponds with the blue slide line on the boat drawing. The orange line on the kite is the Shore line on the boat. By moving the orange line up or down on the kite you can control the angle the kite flies at. In a heavy wind you would move the orange control line higher on the blue line to reduce the angle of the kite in the wind so you could control it. In a low wind the opposite would apply so you could catch more wind so it would fly. On a keelboat in fast water you reduce angle of attack and in slow water you increase it using the same method. You are literally flying the keelboat upstream. It does get a little more complicated on a keel- boat because you need to make these changes while underway.

We accomplish this (I believe the same way they did) with a control line shown as a dotted line on the drawing and named Line #1. It works like this; the line starts near the mast base within reach of the onboard crewman working with the Cordell lines stationed at the box marked A. From there it runs through a pulley (preferably) or a ring near the bow of the boat marked B and up to the slide ring on the slide line. It is tied securely to this slide ring and then continues back to location A once again within easy reach of the crewman. This is what we have found: if you have a couple of very stout guys forward during a Cordell they can force the slide ring to change position by pulling hard on the control line back or forward. It is much easier to shout to the guys on shore to slack the line and then very quickly make the required changes. If the steers- man needs to move the boat further away from the shore you would move the slide ring toward the stern. If you wanted to run closer inshore then you move it forward. If the current is slack you can run with the ring more toward the stern but if she picks up you have to slide it forward. Now, while all this ring positioning is going on you are confronted with another problem; shore debris and brush. In order to safely get the Cordell rope over this stuff, you have to have it higher above the water than the gun- nels of the boat. The gunnels is the ideal height to Cordell from but sometimes it just is not high enough. This is accomplished by having the stern end of the blue line, the slide line attached to the metal hardware holding the yard to the mast. In order to raise the slide line you simply raise the yard on the mast. Once again it is much easier if you get the guys on shore to slack for a moment. Now you have the yard raised to a suffi- cient height to clear the upcoming debris, and the guys on shore have laid into her again and all of a sudden the boat heels toward the shore which in turn drives the chine deeper on the shore side. Often the boat will wheel away from the shore and the steers- man cannot compensate with the rudder so you have to make a quick change to the slide ring before you “warp out” and flounder in the current.

Cordelling is the most effective method of propulsion and the most complicated and at times the most difficult. To safely accomplish it you need 5 to 10 guys on shore and at least two on board (four is better) to accomplish a successful Cordell which might not last long if the shore line goes to pot around the next bend. Then you have to get these guys back on board and pull in about a hundred foot of heavy wet line. Very time consuming stuff.

Rowing; First I would like to point out that you cannot row a full size replica boat against the current and make any headway up stream for long. Even in a very mild cur- rent of 2 to 3 miles per hour you eventually wear out. I have had 20 guys rowing a 60 ft replica on a lake and they are physically depleted after an hour unless they just pace themselves and we ease along at 2 MPH. So why bother rowing if it’s worthless?

Let me explain it this way. In 2004 I was aboard one of our replicas going up the Missouri with the help of a motor boat lashed to our port side. near the stern. I had twenty college students on board as part of a course I was helping to teach at the University of Bismarck. My handy dandy GPS unit indicated we were making 5 MPH. I suggested that all the kids grab an oar and row at a pace they were comfortable with, one which they could maintain for a few hours if need be. We gained .8 mph. Not much but if you multiply that by 12 hours per day and seven days per week you will have traveled 67.2 miles further at the end of each week by supplementing your forward motion with row- ing. So I have come to the conclusion that rowing is just good supplemental power gained by guys who might otherwise just be sitting around the deck. In addition rowing can help you with control issues especially when going down stream.

Sailing; When ever they could as this is free motion and they would take advantage of it whenever they could. It really is not sailing as much as air assistance. There is no tack- ing and if the wind is not within 5 degrees of your stern you’ll just crab sideways. This is interesting, on many of the rivers I’ve run, the wind will follow the course of the river sometimes completely through an S curve. I believe that the trees along the bank, the bank itself, and possibly the coolness of the water have something to do with this effect, but whatever is causing it, it does happen very often.

Push poling; Is one of the less effective methods of propulsion, but as often as not the one least disliked by the crew. I think the fact they are up on the main deck and can see very well, their feet are dry, and it is not that difficult since they are using their leg muscles rather than their backs or arms may have something to do with it. There is a bit of a trick to poling which needs to be mastered. The book “The Keelboat Age on Western Waters” says that the men would put their pole in the water at the bow of the boat and push the pole to the stern, then walk to the front and repeat the movement. This description basically covers the movements but lets add some “lost” details. Your at the bow and you put your pole in the water and boy will you get a surprise as it floats away!

You’re going to be in no more than 4 ft of water which is just about the maximum allowable for successful push poling. What is required is that you must thrust the pole through the water and into the bottom which I might add must be solid, not muddy, and you must do it in one swift motion as the pole is wood, the water is moving, and hopefully so is the boat. We call it “sticking the pole”. Then your not pushing the pole to the stern, but rather your pushing the boat out from under you until you’re at the stern; the pole never changes its position. Then you simply let up on the pole and it will bob to the surface unless its stuck in mud in which case you shouldn’t be poling anyhow. While your heading for the bow (quickly) as your losing forward momentum this whole time you simply trail the pole in the water until you reach you start point again. Then you pick the pole straight up and stick her again. Five guys per side on a 60 ft boat is about right.

More and they are stumbling all over each other and fewer isn’t enough in moving water.

Kedging and Warping; These two terms identify the act of taking a line upstream and either having it secured to the boat at the bow and pulling the boat or attaching the line to something like a tree or large rock and pulling from the boat. This becomes neces- sary when the river narrows and the current picks up speed as it rushes through the narrow spot and you have to go through it. So which term is which? After researching this stuff for 30 years I’m still not sure although I think it may have something to do with whether or not your on the ocean in salt water or inland on a river. The Mariner’s Dictionary describes Kedging as: moving a vessel by heaving in on a kedge rope or warp fast to a kedge anchor that has been carried out to a desired position by a small boat. In the same book, Warp is described as: a light hawser used for warping; to haul a vessel by an anchor [Kedge] carried ahead or by a line [a warp] carried to a buoy or wharf. So if your completely confused now, join the club. It works when it needs to that’s good enough for an old River Rat like me.

Bushwhacking; is when you run the boat up along the bank and grab hold of tree limbs, grass hanging over a bank or anything else you can latch onto and you pull the boat ahead.

These are the basic methods used for upstream travel. Which particular method or combination of methods you use at any given time is determined by the conditions you’re in. If you have wind from the right direction, use the sail. If your in shallow enough water and the bottom is hard, push pole. If your shore line is clean and can be walked on, you run out your cordell. While cordelling, you can put some men on the shore side of the boat to row and while bushwhacking you can have some guys poling or rowing on the river side and so on. It’s whatever works at the time. When going down stream the only two methods you can use are sailing and rowing. Your traveling too fast for any of the others. Now, you will have a couple of guys stationed near the bow with push poles to fend off snags and maybe help with steering a little, but they remain stationary and just use the poles in small areas.

The main issue with downstream travel is stopping. It can be very hard to do when you want to and disastrous when you don’t. You can get so high on a hidden sand bar that it would take an act of Congress to get you off! Stopping when you need to usually does not happen quickly but must be planned out a little ahead. Maintaining control of the boat during a downstream beaching is tricky. A line on the stern—shore side is carried to the shore by a brave soul who jumps to shore or near it when you are very close and quickly throws the line halfway around a tree or rock or something else very solid and pays it out as the boat slows down. Lashing it down solid will usually end up in a bro- ken line or a cleat torn off the boat. Believe it or not a wet natural fiber rope is stronger in a sudden stretch scenario than a dry one as it will stretch and tighten before it breaks and that could make the difference. My crew was coming into Sioux City

a few year back and were running in a channelized section of the river. They were clipping along at a pretty good rate and from the shore I could tell they were not going to be able to stop where they needed. They had thrown a 3/4 inch line to shore to several bystanders but none had caught it. By now the line was soaked and heavy and they were fast approaching this fat old man (me) who would be their last chance to get stopped. By now they must have been getting desperate as they attached a weight to the rope to be sure and get it to me; which almost cold cocked me as it whizzed past my head. I snagged up the line and ran to a near by piling. There would be no time for a slow down so I half hitch her up and just in time as she drew taught instantly. Well, it worked and we got her stopped in about five feet, all 8,000 plus pounds of her. Oh, and by the way that wet 3/4 inch rope was bone dry and about 1/2 inch in diameter.

After all these years of messing around in these old pre-steam era river boats I have discovered one thing for sure:

It’s for young guys not fat old men……….. Keep your powder dry

Butch “Mr. Keelboat” Bouvier